|

Agriculture has always been important to the community, with rich soil that supports diverse crops such as turnips,

beans, and a variety of grains.

THE RURAL HIERARCHYThe following information has been reproduced with permission and grateful thanks to the authorsGRIEVE or STEWARD was the ‘foreman’ who gave the farm servants their daily orders and supervised their work. Especially on the very large farms, the servants might often see little of the farmer who used the grieve for passing on all instructions and for receiving reports of how work was progressing. Many grieves worked alongside the servants to ensure a proper pace of work. Not surprisingly, many grieves were not much liked by the farm servants! PLOUGHMEN were the most highly skilled of all farm servants and so can be seen as being at the pinnacle of farm servant society. Ploughmen also had their own internal hierarchy so that the best, most experienced man was the first ploughman (who usually had the best horses as well), then the second ploughman and so on down the line. Ploughmen tended to be quite a proud breed and often felt aggrieved if given work not involving their horses. Ploughing took up a lot of their time since fields were usually ploughed multiple times each season. Each ploughman looked after his own horse pair. CATTLEMEN The cattlemen also saw themselves as skilled workers and some would have put themselves on a par with the ploughmen - although the latter would have disagreed! When cattle were indoors or in farmyard cattle courts in the winter, there was a lot to do - mucking out (which some farmers insisted on being done every few days), putting in fresh straw for bedding, feeding the beasts hay and chopped turnips and, sometimes, having to go out to the fields themselves to fetch turnips. And they were always alert for illness among the beasts. Cattlemen would sometimes need help from the orra-men at busier times. SHEPHERDS were usually quite independent figures, especially if their cottage was somewhere out in the hills, well away from the farm. Even the grieve might have only occasional contact, trusting the shepherd to get on with the work. When sheep had to be clipped or dipped, the shepherd needed extra hands but, otherwise, he tended the flocks out on the hill pastures in all weathers, watching out for predators and disease and moving the sheep around as required. On farms where the sheep were in fields in closer proximity to the farmyard, the shepherd’s work would be not so demanding. ORRA-MEN ‘Orra’ means ‘other’ or ‘extra’ and so the orra-men were the servants who did all the other, mainly unskilled jobs. Their work was vital at the busy times of year - hay cutting, grain harvest, potato and turnip lifting - but there was an endless round of other tasks. There were dry-stane dykes to be built or repaired, hedges to be cut (using the hedge knife), ditches to be dug or cleaned out, manure or lime to be spread on the fields, buildings to be kept in order. The list would be endless. Where a horse and cart was required for any such work, they spoke of the ‘orra’ horse; one of the ploughmen’s horses would hardly be used for such menial jobs!

BONDAGERS It was universal practice throughout Northumberland for farm servants -

especially if they were living in one of the farm cottages - to be required to supply a ‘bondager’. This was a woman,

often the servant’s wife or an older daughter, who worked in the fields on any days when the farmer/grieve required

that extra labour. On many farms, the bondagers would find themselves out on at least half the days in the year and

sometimes more than that.

HINDS There is confusion about the meaning of this word. Sometimes it refers to all farm servants and sometimes only to skilled workers.

MARCH HIRINGSFarm servants were often only employed for one year. To get another job on a different farm, they had to attend the annual March Hirings in places like Wooler, Alnwick or Berwick.The workers and the farmers gathered together in the market square. The workers would stand around waiting to be approached by a farmer when, hopefully, they would make an agreement. The farmer would then pay the worker a small sum to start work with him later in May The servant's chances of being hired were greatly increased if he could offer a bondager too. At the hiring fair, work hours and a wage would be agreed for both, as well as accommodation, potatoes, corn and other perks. After the March hirings, came ‘flitting day’when the servant and his family might move home. The new employer would provide carts and horses and the family would pile all their belongings, children, pig, chickens and pets to move to the new farm.

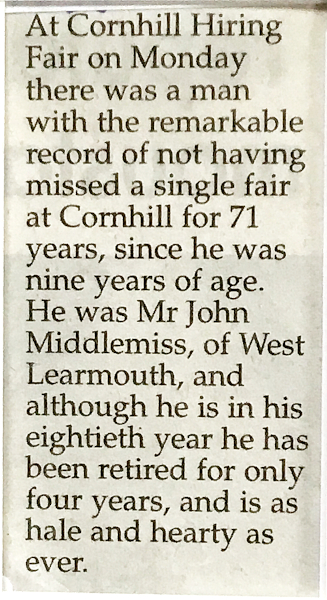

Mike Middlemiss, John's great-grandson notes that, although the hirings were about job vacancies/changing jobs, John remained at West Learmouth for the majority of those 71 years. ACCOMMODATIONMost servants and their families lived rent free on the farm often living in the rows of farm cottages that can still be seen in most Northumberland villages today. Families in the 19th century were usually large and there were wall beds in the downstairs room and some more upstairs, if there was an upstairs. Water had to be carried in pails from a well and there would be a dry toilet outside in a hut. Cooking had to be done on an open fire. Later there may have been a hot water tank and an oven on either side of the fire. The families usually kept a cow, a pig and some hens. They would be supplied with potatoes and grain from the farmer and would be able to grow vegetables.The hours were long and the work often back-breaking and needed to be undertaken in all weathers but, mostly, they were healthy and well-fed.

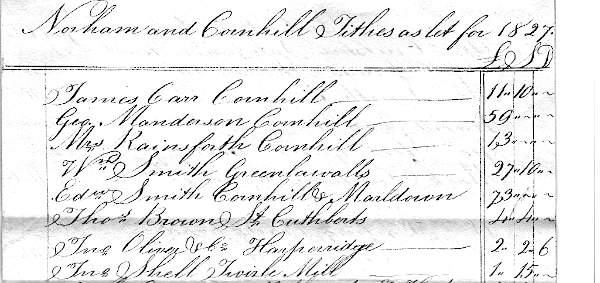

Tithes in 1827A tithe is a one-tenth part of something. Today, tithes are normally voluntary, but historically, they were required and were sometimes paid in kind, such as agricultural produce.

Farmers in and around Cornhill 1897taken from History of Northumberland, edited by T.F. Bulmer, published 1887, provided by Dick PalmerAlexander Coutert - Cornhill Mill Dickson Brothers - Campfield John Lumsden - Castle Heaton Mill Thomas Nevins - West Heaton Eleanor Robertson -New Harper Ridge and Oxendean Burn Robert Scott - Cramond Hill W. W. Smith - Melkington James Whittle - St.Cuthbert‘s and New Harper Ridge.

|